KT Sivakumar, also known as Anton Master, is a prominent early member of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and a close associate of leader Prabhakaran. He significantly contributed to the LTTE as a member of its Central Committee and as the founder and head of the Military Office (MO), enhancing the group’s military effectiveness. Known for his reticence in media interactions, Sivakumar prefers ‘dialogues’ over interviews. The following is a part of a series of dialogues I had with him, providing rare insights, which will be featured in the forthcoming issues.

Rapid Surge and Leadership Crisis in Tamil Militant Groups Post-1983

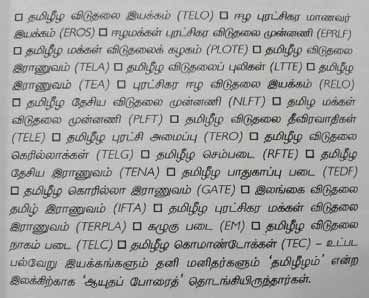

After the ethnic riots of 1983, all the militant organizations, including the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam (PLOTE), Tamil Eelam Liberation Organization (TELO), Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF), and Eelam Revolutionary Organisation of Students (EROS), experienced exponential growth. These groups grew disproportionately large, a situation not fittingly described by the Tamil phrase ‘விரலுக்கேத்த வீக்கம்’ (a swelling that fits the finger), their expansion was beyond what was manageable. Many people joined these movements, and their leaders quickly became seen as heroes.

and Balakumar (EROS) Unite with Prabhakaran (LTTE) in Their Quest for Eelam. Later, Sabaratnam and

Pathmanaba were killed on the order of Prabhakaran, while Balakumar disbanded his EROS, accepting

Prabhakaran’s leadership to save his life, and became a part of the LTTE.

However, the mindset of those who joined after the 1983 riots was predominantly marked by a mix of desires for revenge, anger, confusion, and an overestimation of Indian support and training. Joining these movements became a matter of pride. Yet, there was a general sentiment akin to, ‘I don’t know where we’re going, but judging by the size of this crowd, it must be good!’ kind of Fk;gypy; Nfhtpe;jh mentality, or “Following the crowd enthusiastically.”

Everyone knew there was a need to fight back, but there was uncertainty about who the enemy was, who to target, and who were allies. Knowledge about the Geneva Conventions, war crimes, or crimes against humanity was virtually absent.

Before the 1983 riots, the LTTE and other groups were relatively small and manageable. The mistakes and errors committed were minor. However, after the riots, it became the responsibility of these movements’ leaders

to properly guide the significantly larger number of Tamil youths who had joined. Unfortunately, all these leaders were incapable and immature to lead such a vast group effectively.

Prabhakaran’s Tragic Rigidity: Dragging a Race to Conflict

The liberation struggle should have been more flexible. Leading liberation movements with an ‘Eelam or nothing’ attitude, as Prabhakaran did, is not viable. Prabhakaran believed that anyone deviating from the goal of Tamil Eelam was a traitor, a stance that was misguided. However, he remained steadfast in his goals and never wavered from his beliefs or ideology. He maintained the same ideology from the start of his struggle until his death. His belief that sacrificing one race for liberation led to numerous tragedies

Prabhakaran was indeed prepared to die in the war, but he had no right to drag an entire race to death with him. This was his significant mistake. Nevertheless, I still regard Prabhakaran as an honest man. Unfortunately, he lacked the right advisors; those around him were merely yes-men. Additionally, he was not in a position to accept advice from anyone else.

Prabhakaran’s Leadership: Where Flattery Overshadowed Merit

There were situations where flattering Prabhakaran could lead to higher positions in the organization. I agree that, to a certain extent, he was susceptible to praise and loyalty, and merit became secondary for him.

I will tell you about this as an example. Lawrence Thilakar, who worked under me in my Military Office (MO), was a trainee in the third regiment of the LTTE in Salem camp and had joined the movement after coming from France. From what I observed, he lacked nationalist thoughts for ethnic liberation and was filled with extremist terrorist ideologies.

Our military office then published ‘Porkkural’ (Voice of War), a magazine. However, it would be more appropriate to call it a textbook rather than a magazine. These military textbooks became mandatory reading in all LTTE training camps. During my tenure with the LTTE, nine volumes of ‘Porkkural’ were published. Lawrence Thilakar suggested that we publish an article about the King David Hotel bombing in 1947 by the Jewish terror group ‘Irgun’ during the Jewish insurgency against British rule in Palestine. However, I refused, explaining to him that this was not an appropriate way to educate the LTTE cadres in training camps.

In the first issue, I wrote an editorial explaining what the LTTE’s military office should do, our ideology, and how we plan to achieve our objectives through it. In that editorial, Lawrence Thilakar asked me to write that we run this military office under Prabhakaran’s leadership and guidance. I refused to do so. I said that MO is a work of collective teamwork of many hardworking people. We should promote team spirit, not individuality. It is not an individual action but a group action. Therefore, I said that there was no need to praise Prabhakaran overly. Yes, Prabhakaran’s office is within the MO, but it has nothing to do with the day-to-day operations of the MO.

But Lawrence Thilakar must have misrepresented this to Prabhakaran. Two days before the magazine was set to go to print, Prabhakaran suddenly called me and asked me to meet a prominent supporter in Mumbai for political work. Despite having no involvement in political tasks, I flew to Mumbai. I ended up spending two unnecessary days there. When I returned to Chennai, the textbook had already been printed, and the editorial included words praising Prabhakaran’s leadership and ideas in managing the military office, just as Lawrence Thilakar had suggested.

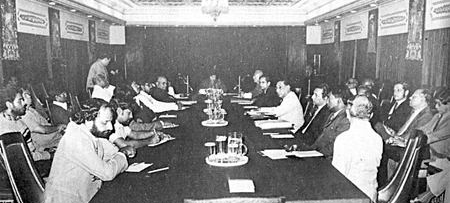

1985, during the Thimpu talks between various militant organizations, including the LTTE and the Sri Lankan government, Prabhakaran sent Lawrence Thilakar with me. However, Thilakar was very junior. There were many more senior members in the organization than he. Anton Balasingham was then responsible for the political wing, and many people were in his division. But Prabhakaran sent Lawrence Thilakar, a ‘yes-man’ to him, for the talks with me. The reason for this was Thilakar’s flattery and his closeness to Prabhakaran.

An incident about Thilakar during the Thimbu Talks is to be noted. All the Tamil parties agreed to line up based on the “4 Thimpu Principles”. At the negotiation table, Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) leaders Amrithalingham, Sivasithamparam, and EPRLF Varadaraja Perumal lambasted the Sri Lankan delegation by lecturing them in history lessons. Thilakar could not be found in his hotel room during the absence of talks. Then I found out he was chasing behind Varadaraja Perumal, begging him for a ‘speech script’ he wanted to deliver at the negotiation table. I stopped his nonsense and reminded him that he was representing the LTTE, And I said that by his action, he was disgracing himself and the LTTE. I did not report this incident; otherwise, his career in the LTTE would have ended with zero.

I am a witness to Prabhakaran’s great affection for the Muslim community. He always emphasized to me the importance of treating Muslims fairly and ensuring they receive their rights. His favourite places to eat were also Muslim-run shops, particularly one we nicknamed ‘Mokka Kadai’, located in the heart of the Muslim area. Another favourite was near the Tirunelveli Junction, close to the Jaffna campus. After watching the first or second show of English movies in the evening, we often visited there for Kottu Roti.

However, when I was in Canada in 1990, I was shocked to learn that the LTTE had expelled the Muslims from Jaffna on the orders of Prabhakaran and seized their property. It was then that I came to know that some of the leading members of the LTTE from the East, like Karuna and Karikalan, met Prabhakaran and changed his mind about expelling the Muslims. LTTE leaders from the East may have influenced Prabhakaran.

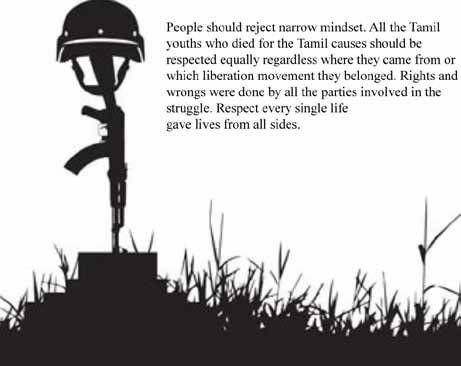

Equal Respect for All Martyrs of Tamil Liberation

I steadfastly refuse to accept the designation of LTTE martyrs as heroes while those from other liberation movements are labelled as traitors. Every individual who fought and sacrificed their lives for the freedom of the Tamil people in Eelam deserves respect and remembrance, regardless of their movement or organizational affiliation.

The practice of solely commemorating the LTTE while neglecting others must be discontinued. Now is a crucial time for Tamils to seek reconciliation and foster unity amongst themselves. It is a vital responsibility of the Tamil community.

By exclusively commemorating the LTTE annually and categorizing members of other movements as traitors, we only deepen the divisions within the Tamil community. We must adopt a collective approach to memorialize all those who laid down their lives for the liberation of the Tamil people without any bias based on their affiliations. This stance is non-negotiable for me.

I expressed this sentiment a year ago on my Facebook page when I observed the unequal valuation of different individuals’ lives.

To be continued…..