Early Days and Initial Activism

Ponnamman, a senior member of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), was a dear friend of mine from our days at Jaffna Hindu College. Our friendship, which initially began with a confrontation at the college, grew stronger over time. In 1973, along with Ponnamman, Chera, Thave, and a few others, we formed a group called the “Try Science Association” with ambitious plans to develop anything that could be useful for liberation efforts. One of our significant projects was the development of a prototype biplane. We managed to construct the basic framework and skeleton, including a propeller. Unfortunately, the project was eventually halted due to financial constraints, and the group disbanded as members went on to pursue university education or moved abroad.

Introduction to Prabhakaran and Philosophical Divergences

In 1977, Kumanan alias Kumanasami, an acquaintance I met regularly in the Jaffna Public Library reference section, introduced me to Pirabakaran. His brother was already a member of LTTE. Kumanan was one of thirteen members who split from LTTE and formed the People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam (PLOTE) organization.

Influence of Global Terrorism and Prabhakaran’s Stance

The seventies were the heyday of terrorism committed by many Palestinian militant groups such as the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), Black September Organization (BSO), Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), Japanese Red Army (JRA), Palestine Liberation Front (PLF), etc. They were involved in extreme terrorist activities, including hijacking planes, bombing public areas, kidnapping and murdering civilians, and targeting sports figures. These actions were globally condemned as acts of terrorism. Prabhakaran must have been influenced by the terrorist activities of Palestinian groups. When I met him for the first time, he said, “Liberation can be achieved only through terrorism.” This statement really affected me. I countered that terrorism would not help our quest for national liberation. The acts of terrorism by the Palestinian movement have, in fact, significantly damaged all liberation movements around the world. These actions cast suspicion on them worldwide and blurred the lines between genuine liberation struggles and terrorism.

Prabhakaran’s Character and Leadership

At that time in 1977, I had not joined the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). Our meetings usually happen at public places like temples, bus stands, and libraries. When we met at the bus stand, Prabhakaran would arrive on a bicycle and take me with him, and we would chat while peddling. Prabhakaran and I became close to the extent that he would leave his gun at my house when he visited. He trusted me to that level.

Prabhakaran’s Admiration for Historical Figures and Ideals of Martyrdom

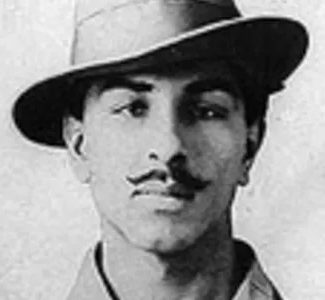

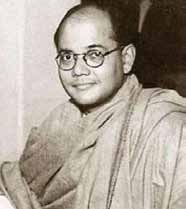

Prabhakaran possessed a laudable quality: an eagerness to learn and a deep passion for reading. He was influenced by and considers Bhagat Singh, Veerapandiya Kattabomman, and Subhas Chandra Bose his role models. He had a particular admiration for Veerapandiya Kattabomman. However, I always viewed Kattabomman as unwise. I frequently debated this with Prabhakaran, arguing that true bravery would have been for Kattabomman to regroup his forces and continue the fight rather than face execution for defying the British tax demands. Prabhakaran, however, did not share this view. He passionately believed in the nobility of martyrdom and the honour of dying on the battlefield. He wished to be remembered as a heroic figure in Tamil history, akin to Veerapandiya Kattabomman.

In 1987, after the Indian army’s arrival in Sri Lanka, Prabhakaran many times said to me, “It’s not wrong for a race to perish fighting for its freedom.” This shocked me. I argued with him: Are we fighting to live or to annihilate our race and ourselves? His belief that a race can die for freedom persisted until the end. He lacked thoughts on sustaining the liberation struggle and ensuring survival. The Tamil literary books he read in his early years influenced his mindset. These books glorified dying in battle, which resonated with him.

During the 70s and 80s, Prabhakaran, other LTTE members, and I regularly frequented the Regal or Rio theaters for the first and second screenings. We had a keen interest in films related to war, history, westerns, and law & order. Hollywood movies often reached Sri Lanka late, premiering in Colombo before arriving in Jaffna. I watched the 1970 film ‘Patton’ at Regal theaters well before meeting Prabhakaran. The film, portraying American General George S. Patton, includes his famous quote during a speech to the 6th Armored Division on May 31, 1944: ‘No bastard ever won a war by dying for his country. He won it by making the other poor dumb bastard die for his country.

Prabhakaran possessed many commendable qualities. He was dignified in his conduct, and I regard him as a true gentleman. I never heard him insult or harshly criticize anyone. However, he was stubborn, adhering to his own inflexible beliefs, akin to the saying, “My rabbit has three legs.” He was not receptive to differing viewpoints. Over time, he developed the conviction that anyone not actively contributing to the LTTE was a betrayer. Initially a liberation fighter with a character of comradeship, he gradually believed in his totalitarian decisions. Prabhakaran’s repeated errors in judgment and misguided decisions led to the unnecessary loss of many young lives and civilians. Thousands were maimed, suffering life-altering injuries, tragedies that could have been avoided. It’s important to acknowledge that the Sinhalese population also endured loss of lives and considerable suffering.

As an individual, Prabhakaran had limited knowledge and a lack of foresight. In my opinion, he fell short in his role as a leader. True leadership carries immense responsibility, particularly when it involves thousands of young people who trust in and commit to the cause, often at the cost of their lives. Prabhakaran failed to fulfill this vital duty, which is my most significant criticism of him.

Confronting Ethical Dilemmas in LTTE’s Strategies

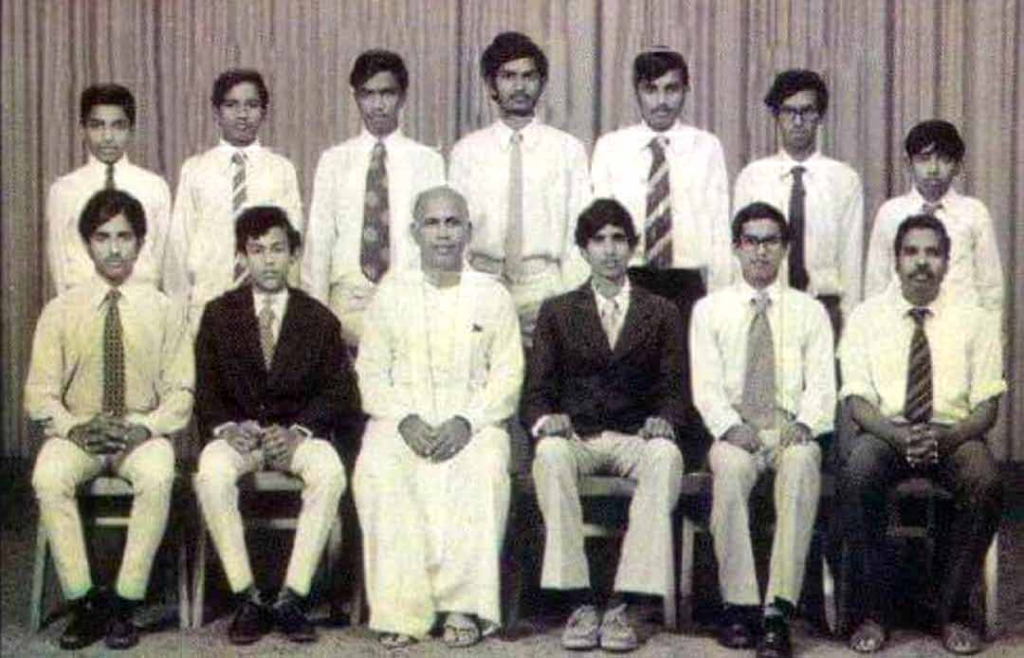

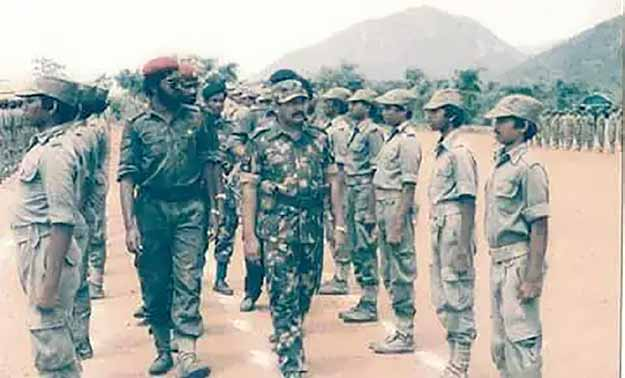

Training Camp, 1983

In 1978, I was in Ponnamman’s house, in his room, along with Prabhakaran. Prominent LTTE members Raghavan and Sellakili were also present, though Ponnamman himself was not there. During our political discussion, Sellakili made a disturbing statement. He said, “Even young Sinhalese children should not be spared. They must be killed. They will grow up to kill Tamils. It’s better to kill them while they are still children.” This statement deeply troubled me. Sellakili, known for his technical knowledge and high regard within the LTTE, advocating such an extreme stance was bewildering. I argued that such actions were unethical and immoral; one should not entertain such thoughts. However, to my shock, Prabhakaran supported Sellakili’s view, stating, “Those children will grow up to kill Tamils, so there is nothing wrong in killing them now.” This stance left me profoundly disheartened. As the argument intensified, Prabhakaran and Sellakili eventually left. Raghavan was also present, and contrary to my expectation that he would support my view, he agreed with Sellakili, asserting the necessity of killing Sinhalese children. Ragavan’s mindset in this regard was deeply shocking to me.

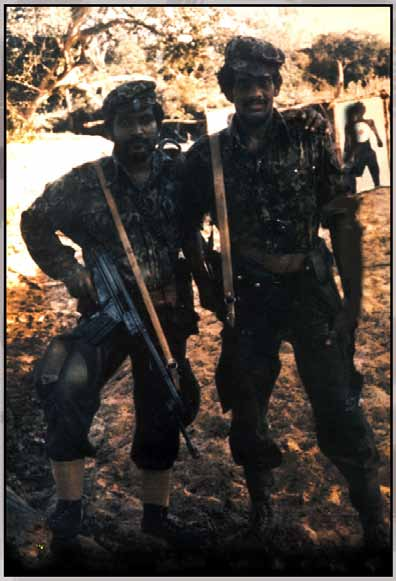

After joining the movement in 1978, My school friend Ponnamman was appointed to oversee the LTTE’s training camps in India starting in 1983. I recall a particular incident when I was at the sixth batch training camp in Mettur, Tamil Nadu. I came from the Military Office (MO) to test my prototype improvised devices: a Claymore Mine and an Anti-Tank Mine, which I named ‘Piglet,’ designed based on the shaped charge concept. During this time, Ponnamman was not present at the camp. In the camp, from a corner, I kept hearing pitiful cries. When I inquired, I found a young man tied with a rope being brutally beaten by the members who ran the camp. When I asked about his inhumane punishment, I was told that he was being punished for trying to escape from the camp. I stopped their beating and made them remove the rope. After several months, I learned the young man had been promised a boat to Sri Lanka. Then he was shot dead in the middle of the sea. This revelation filled me with rage. This would not have happened without the knowledge of Ponnamman and Prabhakaran. Ponnamman was my dear friend; there is no room for disagreement. However, I couldn’t bear the thought of how he could allow this heinous crime. I felt sad and angry with him and thought karma would take its toll. Eventually, Ponnamman died in an explosion while refueling an explosive-laden LTTE bowser in Navatkuli Jaffna.

Anuradhapura Massacre and its Underlying Politics

When I learned of the massacre of 146 innocent Sinhalese civilians in Anuradhapura on May 14, 1985, I was absolutely devastated and sickened. While some argue that the killings were in retaliation for the Sri Lankan military’s massacres in Valvettiturai, two wrongs do not make a right. This act is a war crime and a crime against humanity. But behind this killing, there is a story to tell.

Engagement with RAW and Ethical Confrontations

I was in Puducherry (Pondicherry) during the July 1983 riots when the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) chief contacted me. Later, when Prabhakaran came to India, he established a connection with RAW in Chennai. Subsequently, I decided to break off my contact, but Prabhakaran asked me to maintain it. I stayed connected until I left the LTTE. I would often ride to Pondicherry to discuss various issues. At one point, the RAW officer suggested that the LTTE should massacre Sinhala civilians. I was angered and refuted this idea, stating that our struggle was against the Sinhala regime, not the civilians. When I met Prabhakaran and discussed this issue in Chennai, he informed me that RAW had also made similar requests to him.

A couple of months after our conversation, the Anuradhapura massacre occurred. Balasingam, the official spokesperson, issued a statement denying the LTTE’s involvement in the killings. In my subsequent meeting with the RAW officer, he congratulated me on the brutal act. This left me in a dilemma: either RAW genuinely wanted the massacre to occur, or they were evaluating the LTTE to understand its motives. Following the incident, they might have been reassessing the LTTE, or they might have genuinely been offering congratulations. I cannot conclusively determine their true intentions.

However, I didn’t delve further into the matter. At that time, I was deeply engaged in military development and research at the Military Office (MO). Shortly after the Anuradhapura killings, the first Thimbu Talks commenced. Prabhakaran tasked me with representing the LTTE in these talks alongside Tilakar, who worked in my MO. Years later, two or three of the LTTE who participated in the killings admitted to me that they had conducted the attack and how they had escaped. I have always been vehemently against the killing of innocent Sinhalese civilians.

I came across accusations in the Sri Lankan media that Pulendran, the then LTTE leader in Trincomalee, had been killing Sinhalese civilians. During a meeting with him in Jaffna, I confronted Pulendran about this and sternly warned him that I would shoot him on the spot if he continued attacking civilians. Notably, in the late 1970s, I interviewed both Pulendran and Seelan for recruitment into the LTTE while in Trincomalee. I chose Seelan as a new member but had reservations about Pulendran due to his immaturity. Despite my decision, someone else later recruited him into the LTTE.

INDIAN ARMY’S ARRIVAL, THILEEPAN’S HUNGER STRIKE…

When the Indian Army arrived in Sri Lanka, Tamil people welcomed them with garlands, drums, and music. The relationship between the Indian Army and the Jaffna people was initially cordial to the extent that if the LTTE attacked the Indian Army, the people themselves would retaliate against the LTTE. Prabhakaran wanted to disrupt this friendly relationship.

You need to understand that we did not initiate an armed struggle by placing our trust in India. India bears no responsibility for resolving the Tamil issue in Sri Lanka. Whether the goal is Tamil Eelam or a federal state, the reality is that a complete military victory is unattainable. Ultimately, all parties must come to the negotiating table. Western powers and the Soviet Bloc allowed India a free hand in dealing with Sri Lanka, a fact made clear to the Tigers by both blocs. India achieved its objective by bringing Sri Lanka under its foreign policy influence through the India-Sri Lanka Agreement (an agreement between India and Sri Lanka, not with the LTTE).

Part of the Indo-Sri Lanka Treaty recognized the traditional land of the Northern and Eastern Tamils of Sri Lanka and annexed it as a province for the Northern and Eastern Provincial Governments. Many unresolved issues are left for future negotiations regarding the devolution of power for the Tamil province. Prabhakaran was wrong if he expected India to hand Tamil Eelam on a silver platter. It was Prabhakaran’s fault if he misguidedly believed Tamil Eelam could only be achieved through 100% military victory without foresight.

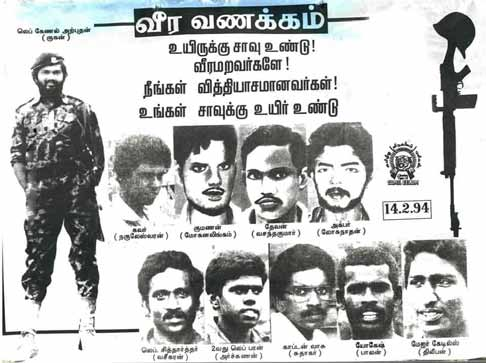

During the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord period, it’s a fact that the LTTE secretly brought in an arms shipment without the knowledge of both the Indian and Sri Lankan governments, despite LTTE’s denials. On one side, the LTTE feigned the surrendering of weapons to the Indian Peace-keeping Force while simultaneously smuggling in arms. The Sri Lankan Navy’s interception of this shipment led to the arrest of 17 LTTE members, including Kumarpappa and Pulendran. Many, like Pulendran, had merely gone to view the ship. Prabhakaran exacerbated the situation by providing cyanide capsules to these 17 members on October 5, 1987. Tragically, 13 of them died. I view this cyanide incident as an unnecessary loss of life.

Prabhakaran created all the violations and dramas to destroy the entire process. Thileepan might have genuinely desired to sacrifice his life, hoping to achieve something beneficial for the Tamil people. However, Prabhakaran manipulated Thileepan’s intentions for his own political ends. I was with Prabhakaran on the day Thileepan began his hunger strike. Prabhakaran asked Kasi Anandan and me to escort Thileepan to the hunger strike site in Nallur. After Thileepan’s death, Prabhakaran directed Kasi Anandan and me to hand over his body to the Faculty of Medicine in Tirunelveli. I conveyed his body there, where Rajini Thiranagama, head of the Department of Anatomy, along with the other Doctors, received it.

The five demands made by Thileepan during his hunger strike were not major or complicated. The solution was on the card of the Indo-Sri Lanka accord. Forming an interim government and confining the Sri Lanka army back into barracks, etc., needed some time to settle. Both Thileepan’s hunger strike and the cyanide incident were orchestrated by Prabhakaran to incite the Tamil population against the Indian army. This strategy ultimately proved to be successful.

Evaluating the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord and LTTE’s Strategy

India is not the adversary; Prabakaran deliberately orchestrated the prevailing situation. As a result, the Tamil community now endures losses far more significant than what they initially encountered, with effects that are expected to linger for two to three generations. Unfortunately, post-1980, the central committee of the LTTE lost its effectiveness, paving the way for Prabakaran to consolidate his position as the sole leader. It’s common for individuals to develop an inflated sense of self-importance upon gaining a modicum of fame and power, a tendency comparable to a ‘messiah complex.’ This complex is characterized by an individual believing they are, or are destined to become, a savior with a grand mission, often leading to a disconnect from reality and rational decision-making.

This Dialogue with Anton Master: to be continued in our next issue