Vinayagamoorthy Muralitharan, widely known as Colonel Karuna Amman, is often recognised as the most skilful military leader in the history of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE)). He joined the LTTE in 1983, spurred by the ethnic violence of that year, and swiftly climbed the ranks to become one of the most trusted bodyguards of Velupillai Prabhakaran, the leader of the LTTE. His career progressed rapidly, and he eventually assumed the role of the commander of the Eastern Province.

Notably, in 1997, amidst Operation Jayasikurui (which translates to Operation Certain Victory in Sinhala), he was elevated to the position of the chief military commander of the LTTE’s infantry divisions, with a command of approximately 40,000 fighters. On July 26, 2004, Karuna Amman decisively broke away from the LTTE and sent approximately 7,000 eastern fighters back to their homes after making them relinquish their arms. This move, stemming from his allegations of the LTTE’s neglect of the eastern Tamil community, marked a critical turning point in the conflict.

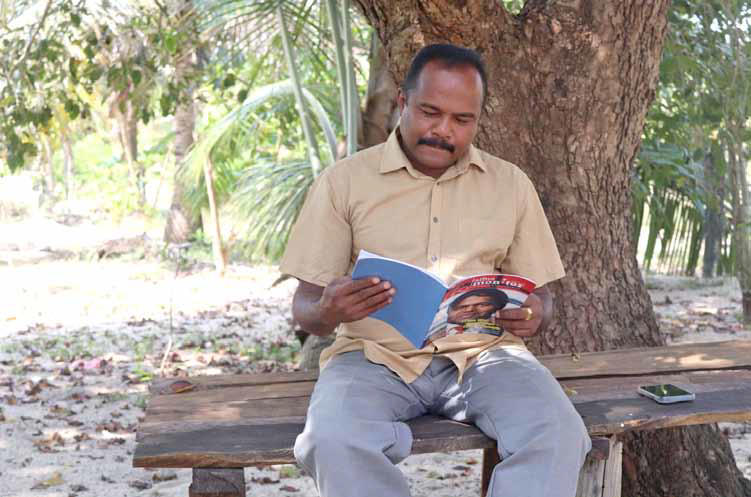

The defeat of the LTTE in 2009 is attributed to several factors, but the departure of a highly skilled commander like Karuna Amman, along with his disbanding of a substantial number of fighters, is often cited as a key reason. This action not only significantly contributed to the LTTE’s eventual downfall but also to the death of their leader, Prabhakaran, and played a crucial role in the conclusion of the 30-year-long Sri Lankan Civil War. Many supporters of the LTTE and related media outlets label Karuna Amman as a traitor, accusing him of abandoning the Tamil Eelam movement. Conversely, numerous parents in the Eastern regions, whose children were sent home by Karuna Amman after laying down their weapons, view him as a hero who rescued their offspring from the severe conditions of the conflict. Jaffna Monitor embarked on a mission to understand the reasons behind Karuna Amman’s separation from the LTTE, traveling to Murakkoddanchenai in Batticaloa for an indepth conversation with him. This exclusive interview offers a comprehensive overview of our dialogue with Karuna Amman. We come from Jaffna, a region where many LTTE supporters perceive you as a traitor.

Conversely, several former LTTE fighters and leaders we have spoken to hold you in high regard, some even describing you as the most capable and brilliant military commander in the LTTE’s history. Can you shed light on the circumstances that led to your departure from the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE)? There are various theories and speculations – what is your perspective on this matter? ‘To fully address your question, exploring the background encompassing my involvement,the LTTE, and the Eastern fighters is important.’

He settled into a comfortable position, crossed his legs, and started to speak with a composed attitude. ‘The LTTE has been a disciplined and strict organisation since its early days; there is no room for doubting this fact. Similarly, I continue to regard the leader of the LTTE, Prabhakaran, as a charismatic leader, and in this regard, there is also no room for argument. It was he who nurtured us. Had there been no Prabhakaran, the name Karuna Amman might have remained obscure. My respect for my leader, Prabhakaran, was, and still is, unwavering. After the July 1983 riots, all movements, including the LTTE, experienced significant growth. During this time, my elder brother Regi and I chose to join the LTTE.

The main reasons for our decisionwere the discipline and control within the LTTE organisation, coupled with Prabhakaran’s excellent leadership skills and the aura he possessed. After the 1983 riots, the Tigers comprised approximately 365 initial members. These members were split into three groups for training and sent to India. I belonged to the third group that underwent training there. Our training camp took place in Kolathur, located in the Salem district of Tamil Nadu, at a farmhouse owned by the Tamil Nadu politician ‘Kolathur’ Mani. The contribution of the then Indian Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, in nurturing the LTTE was very significant. Similarly, the role of the former Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, M.G. Ramachandran (MGR), was also important. There was an excellent relationship between MGR and Prabhakaran. MGR, being a heroic figure, might have admired the heroic actions of Prabhakaran and the LTTE. From the training camps, Prabhakaran would personally select some of the outstanding performers for his personal team based on their physical fitness, behavior, and skills demonstrated during the camp. I was among the few selected from our third batch to be part of Prabhakaran’s team. Immediately after completing the training, I was inducted into his team. Subsequently, I underwent various types of specialised training while being with him. Training specific to bodyguards and intelligence was provided.

I received this training and became a part of the leader’s personal bodyguard team. Prabhakaran had a special fondness for the fighters from the Eastern Province. He often engaged in casual conversations, shared laughter, and played with them. He was particularly

fond of the Eastern slang of these fighters. During that period, Aruna was responsible for the Eastern region. Meanwhile, we were with Prabhakaran in Chennai, maintaining relations with the Indian government and coordinating resources.

In late 1985, when the Eastern commander, Aruna, came to Chennai, he was injured in an accident, leaving a vacancy in the East. Subsequently, Prabhakaran assigned me to go to Batticaloa. This was my first visit to Batticaloa after completing my training. At that time, Kumarappa was the commander of Batticaloa, and I worked under his command. During the Operation Liberation battle that began in May 1987, Eastern commander Kumarappa went to Vadamarachchi with some Eastern fighters, and I joined them. Subsequently, a strategic directive from Prabhakaran altered our operational course.

While initially instructing Kumarappa to stay in Jaffna, Prabhakaran reassigned me to head back to Batticaloa, entrusting me with the expanded responsibility of district commander for both Batticaloa and Ampara. I officially embarked on this role at the onset of July 1987. During my tenure as commander, we instituted and executed numerous strategic and operational reforms. This period was also significant due to the implementation of the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord, a pivotal event in Sri Lankan Tamils’ history.

During the tenure of the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord, Kumarappa and Pulenthiran were apprehended while in the process of transporting a shipment, which included not only weapons but also vital and confidential documents related to the LTTE. These documents held immense value, encompassing international communication records, details of commanders and area commanders, and other critical information. This apprehension took place as they were transferring these sensitive materials from the LTTE’s military office in Chennai to Jaffna by boat. The Sri Lankan government, recognising the strategic importance of the documents over the weapons, intensified its focus on this discovery.

In a dramatic response to their capture, Kumarappa and Pulenthiran resorted to suicide by consuming cyanide. This act precipitated a significant escalation in the conflict between the Indian Army and the LTTE. At this critical juncture, while in close consultation with Prabhakaran, I followed his directives and travelled to Batticaloa. Upon my arrival, I found myself engaged in direct combat with the Indian forces. Almost all commanders of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) harboured doubts about their ability to win a war against India. Key figures such as Pottu Amman, Soosai, and Nadesan cited injuries and eventually fled to India. At that time, Prabhakaran was in the Nithikaikulam forest in Mullaitivu. As the situation escalated and grew increasingly complex, I received a crucial directive from Prabhakaran. The message was succinct and urgent: “The situation is deteriorating; gather whoever is available and proceed to Mullaitivu.” In response, I mobilised alongside my brother Regi, leading a contingent of approximately 150-200 Eastern fighters to Mullaitivu.

Upon reaching the area, we united with Prabhakaran in the Manal Aru forest to defend against the Indian Army strategically. Our foremost goal was safeguarding our leader, Prabhakaran, especially during Operation Checkmate, an IPKF operation targeting his capture or elimination. Together with Balraj, Commander Anbu, and other key members, we created a protective ring around our leader to ensure his safety. Concurrently, the Vavuniya commander Jayam and others coordinated with Maththaiya on the Mallavi front. Adding to our strength, the former Jaffna military commander, Kittu, rejoined our ranks after returning from India. Our confrontation with the Indian forces was intense and determined as we sought to prevent their advance towards Prabhakaran.

Our efforts were singularly focused on safeguarding our leader, Prabhakaran. The battles were fierce, and our resolve unyielding. Despite our tenacious defence, we suffered significant losses, with many Eastern fighters falling during the conflict. During the peak of the conflict with Indian forces, many LTTE fighters had been killed by the Indian troops; some left the movement, while others fled to India. The ones who remained to fight in the forests were our group in the Batticaloa district, Paduman’s team in Trincomalee, and Anbu, Mahathaya, and Balraj also stood their ground and fought. Apart from these, no one else steadfastly supported Prabhakaran. Key figures like Pottu Amman, Soosai, and Banu fled to India without informing the leader. Ironically, those who initially left Prabhakaran later became prominent commanders of the Tigers.

But, they say Pottu Amman went to India for additional medical treatment after being injured…

Medical facilities were available in the forest where Prabhakaran was based. But did everyone who got injured really flee to India for treatment? On one occasion, Prabhakaran jokingly asked his commanders whether Semmalai, the initial point of his base, was nearer or if it was India. Ok.. Then what happened? At a certain point, circumstances led to the withdrawal of Indian forces. Anton Balasingham was a key figure in diplomatically influencing this development. He was a skilled diplomat who adeptly handled numerous challenges on behalf of the LTTE, often saving the organisation from difficult situations.

This is a fact I can confidently affirm to anyone. When the Indian Army opted to withdraw, India’s trust in the LTTE had eroded. Simultaneously, a robust relationship developed between the Sri Lankan government and the LTTE. Following this, the Sri Lankan government engineered circumstances that made it untenable for Indian forces to remain in Sri Lanka. Prior to the withdrawal of Indian forces, groups opposing the LTTE came together to establish the Tamil National Army (TNA), supported by India.

The TNA was mainly stationed in the Eastern Province. Following the withdrawal of the Indian Army, a significant conflict erupted between the TNA and the LTTE. LTTE managed to bring the Eastern Province under control during this conflict. It was, indeed, a horrific fratricide. I believe that the reason for our defeat in the Tamil Eelam struggle was the short-sightedness of the leaders of the liberation movements. All the militant groups were embroiled in conflict, tragically killing each other, allowing the enemy to witness our internal strife with amusement. The capture of the Eastern Province by the LTTE was a pyrrhic victory for the Tamil community. While the Tigers did not suffer a major loss, theconflict resulted in the deaths of approximately 7,000 to 8,000 Tamil fighters from the TNA

Looking back after many years, what are your thoughts now about the LTTE’s elimination of members from other movements? Do you feel a sense of sadness and guilt about the fratricide committed by the LTTE?

I believe that eliminating members of other movements was definitely not the right course of action; it was a grave mistake. We revered our leader, Prabhakaran, and never questioned his commands. We always acted solely on command all the time, often without awareness of the immediate or future consequences. We followed orders without hesitation; as youngsters, we did whatever we were ordered. Even if we had been ordered to commit suicide, we would have done it. That’s how we were brought up in the movement.

Was it brainwashing, Amman?

Undoubtedly, what we experienced was brainwashing. There was a strong allure towards our leader, Prabhakaran, accompanied by a systematic indoctrination that glorified dying for the Tamil race and leader. This mindset was instrumental in the establishment of the BlackTigers. Back then, our understanding was limited. We regarded every order as if it were a divine command.

Please continue…

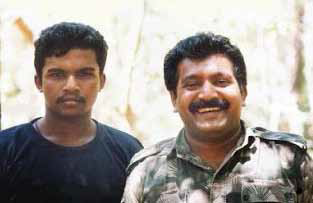

In my view, the defeat of the liberation movements can be largely attributed to a lack of foresight among their leaders. The takeover of the Eastern Province from the Tamil National Army inflicted substantial losses on the Tamil community. The conflicts that began in Pottuvil and spread to Cheddikulam Musalkutti might The formidable Jeyanthan Regiment, once commanded by Karuna Amman. hellojaffnamonitor@gmail.com Jaffna Monitor 13 have been preventable.

It was a situation where both sides were primarily focused on mutual destruction. Had there been better understanding and communication among the leaders of the Militant organisations, such losses might have been averted. Mistakes were made on both sides, with a notable fault lying with the LTTE. The leaders should have been more contemplative about their strategies. As for the fighters who were merely executing orders, how could they have recognised the error of their actions in the heat of the moment? We did not fully grasp the severity of the situation when the LTTE eradicated Tamil Eelam Liberation Organization (TELO) in 1986, leading to the loss of hundreds of our Tamil brethren, nor did we comprehend it when Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF) suffered the same fate at the hands of the LTTE within the same year.

My firm belief is that all fighters who took up arms for the cause of a separate Tamil nation, irrespective of their group affiliations, deserve honour and recognition. Our enemies skillfully and systematically nurtured a sense of hatred among us, turning us into unwitting victims. The young men who embarked on a mission to fight for Tamil Eelam against the Sinhala chauvinist government tragically found themselves in a dire situation, compelled to surrender to the very forces they opposed. This is a shameful incident in the history of the Tamil struggle.

What changes occurred within the LTTE following the departure of the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF)?

Following the departure of the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF), the number of individuals joining the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) from the Eastern Province significantly surpassed those from the North. This was partly due to the disillusionment among Northern people caused by internal conflicts and killings within the movements.

Many North parents were more inclined to send their children abroad for safety amid these circumstances. During this period, the Eastern Province faced severe military impositions and witnessed numerous massacres. As a result, many youths from the Eastern Province joined the LTTE. In 1993, under my command, an elite infantry formation named the Jeyanthan Regiment, comprising highly skilled fighters from the Eastern Province was established. The motto of the Regiment, ‘vq;Fk; nry;Nthk;. vjpYk; nty;Nthk;>” translates to ‘We will go anywhere.

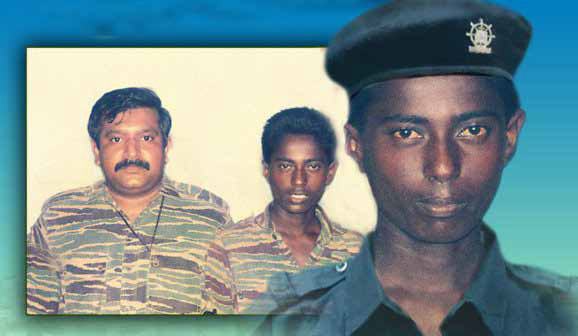

We will win at anything.’ The Jeyanthan Regiment, named in honour of Jayanthan, the first Sea Black Tiger from the Eastern Province, was renowned for its exceptional combat capabilities. Strategically positioned in the North, the Regiment played a crucial role in ensuring the safety and protection of the LTTE leader, Prabhakaran. The fighters selected for this Regiment were frontline combatants, adept at safeguarding the leader under any circumstances. This Regiment was instrumental in executing several major operations. These included the Battle of Pooneryn (Operation Frog), Operation Unceasing Waves, targeting the Mullaitivu army camp, Operation Jayasikurui, and many more. These operations highlighted the Regiment’s crucial role in the LTTE’s military strategies and its significant contribution to the organisation’s combat efforts.

The mainstream Tamil media Often overlookthe contributions of fighters from the Eastern Province in the northern battles. The fighters from the Eastern Province often met their end far from home, in the Northern Province, rather than in the East. There was a scenario in the East: when our regiments prepared to embark on their journey to the North, the parents of the fighters would come and wail in front of my camp, pleading with me not to send them to the North.

The North was known as the ‘killing fields’ for the Eastern fighters. After the fall of Jaffna to the Sri Lankan government forces in 1996, the LTTE relocated its primary operations base to the Vanni region. In a significant turn of events, the LTTE seized the Mullaitivu army camp in Operation Unceasing Waves. This camp was the only government-held base in Vanni and was captured just three months after the Jaffna Peninsula fell to government forces. This critical triumph in Operation Unceasing Waves, which resulted in the loss of hundreds of fighters from the Eastern Province, allowed the LTTE to gain complete control over the entire Vanni region. While the Sri Lankan government forces maintained control over the northern tip of Jaffna, their supply lines to the south were heavily dependent on sea routes, as the land route, including the A9 or Kandy Road, from Vavuniya (under government control) to Jaffna, passed through LTTE-controlled territory in the Vanni.

In a strategic move to secure this vital route, the Sri Lankan army initiated ‘Operation Jayasikurui’ on May 13, 1997. Had Jayasikurui succeeded and the A9 has been captured, it could have marked the end of the LTTE. Before ‘Operation Jayasikurui,’ the Sri Lankan army had executed ‘Operation Edibala’ to take control of the main road from Vavuniya to Mannar. I recommended to our leader, Prabhakaran, that we avoid a direct counterattack. Instead, we adopted a strategy of feigning defence while strategically retreating, thus creating the illusion that we were incapable of a counterstrike. This approach tied up about 10,000 army personnel in ‘Operation Edibala.’ The army’s preoccupation with this route was a deliberate part of my plan to divert their attention to a less critical location.

Prabhakaran agreed with this strategy. Once successful, it was apparent that the Sri Lankan army’s next objective would be to capture the A9 highway. The control of the A9 highway was critical. If the A9 highway were to be captured, the Vanni region would have easily fallen into the hands of the government forces, effectively making it impossible for the movement to continue. Indeed, during the final war, the moment the Sri Lankan army seized control of the main A9 highway marked the technical defeat of the LTTE.

Prabhakaran convened a meeting with all commanders to discuss the battle. During the meeting, the Jeyanthan Regiment proposed that Eastern Province forces should be tasked with offence rather than defence. The other LTTE commanders, frightened by the recent loss of Jaffna, readily accepted this suggestion despite the high risk of casualties and destruction it carried. Meanwhile, the Jeyanthan Regiment organised approximately 2,000 fighters from the Batticaloa district and 600 from the Trincomalee district to counter the Jayasikurui attack. The defence was set up under Theepan’s leadership. On the first day, Theepan’s fighters lost one kilometre. On the second day, another kilometer was lost, and by the third day, Theepan’s defense team had retreated a total of three kilometers. The Sri Lankan army advanced close to Puliyankulam.

Jeyanthan Regiment had not yet started the attack. Within the organisation, other commanders began criticising them, questioning when they would begin to attack. Instead of confronting the advancing army from the front, they circled around to the back and attacked from the side at Thandikulam. A fierce battle ensued. The army suffered significant losses, and the war was halted for 12 days. The Thandikulam battle caused substantial damage to the army.

The BBC described it as ‘LTTE entered the battlefield from the back, like an elephant entering a cornfield.’ The army began advancing again, and in response, the Jayanthan Regiment led another attack, inflicting heavy damage on them. This resulted in the battle stalling for 22 days. At this juncture, Prabhakaran began to believe we could win the war. Then, one day, he summoned us to Puliyankulam. Up to that point, our fighters had not seen the leader, and there was an intense desire among them to meet him. Remarkably, about 180 of our fighters had already fallen in the Jayasikurui battle without having seen him. Prabhakaran had invited all the commanders to this meeting, although the reason for his summons was unclear. He also brought delicious food for the fighters.

Prabhakaran ascended the stage, and a sense of anticipation filled the air. With a commanding presence, he began to speak. In an unforeseen turn of events, he announced that I, Karuna Amman, was to be elevated to the prestigious role of the overall commander of all LTTE infantry divisions. The weight of his words hit me like a thunderbolt. Such a monumental appointment had never flickered through my mind, not even in the most ambitious corners of my imagination. As Prabhakaran’s words resonated through the meeting hall, I couldn’t help but notice the air of dissent that began to brew subtly among some of the commanders. A few commanders present at the meeting, including Pottu Amman, the head of the LTTE’s intelligence wing, visibly did not welcome this decision, as was evident from their facial expressions. I also somewhat realised that this appointment could lead me into unnecessary trouble.

To be honest, I had no desire to take on this responsibility. From that day forward, key figures within the LTTE, like Pottu Amman, began to harbour resentment toward me. Pottu Amman, armed with his keen strategic acumen, began to quietly yet effectively marshal support from other LTTE commanders against me. It was as though he was skillfully constructing a labyrinth of opposition around me and began digging a pit against me.