Translated from the original Tamil short story mika uḷḷaka vicāraṇai (மிக உள்ளக விசாரணை) by Shobasakthi. The original story is available at his website. If you have any questions or feedback, please contact ez.iniyavan@gmail.com.

There is one commonality and one difference between this story and the famous novel by Franz Kafka. They are both about judicial inquiries: the title of his novel is ‘The Trial’ and the title of this story is “The Very Internal Investigation.” The difference is that although Kafka’s hero was not afforded the honor of having his last name spelled out, at least Kafka denoted it by the letter ‘K.” Our hero did not even deserve that. Now let us dive straight into our story.

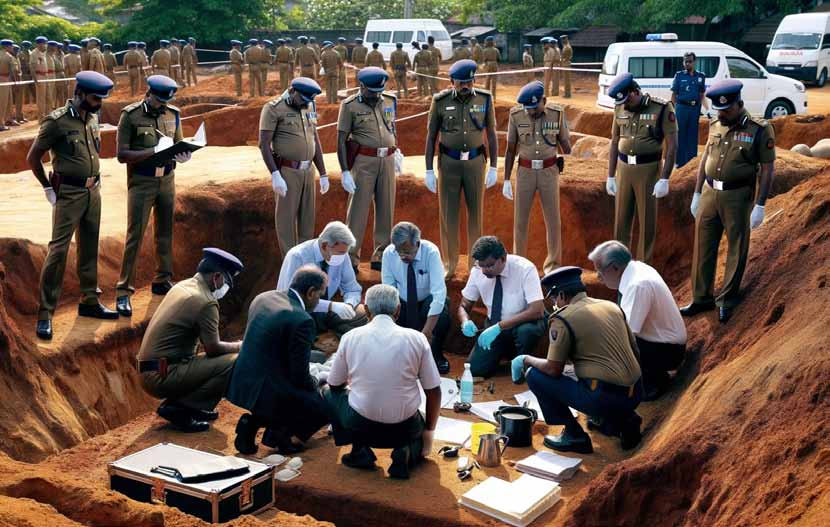

This story begins abruptly with the discovery of a twenty-five year old mass grave from which eighty five human skulls and heaps of human remains were excavated.

The village of Maṇkumpāṉ lies four miles from the city of Jaffna. That is where the primary center for drinking water supply for the Jaffna archipelago is located. In March of last year, work began to lay underground pipes for supplying drinking water to Puṅgudutīvu. Excavating the first two miles of ground from Maṇkumpāṉ to lay pipes is not a difficult task. The soil in Maṇkumpāṉ is soft, moist, almost flowery, fine sand. Digging the soil is as easy as digging water. But beyond two miles, the soil turns into a hardened mixture of clay and conch shells. Digging and laying down pipes becomes arduous. The village where such hard ground begins is called Ūripulam.

When the employees of the Water Supply and Drainage Board used modern heavy equipment to excavate the soil in Ūripulam, they discovered the mass grave with eighty five human skulls and other human remains. The police from Kayts showed up right away and set up barricades around the mass grave. Neither the public nor the media were allowed near the site. When a Tamil Member of Parliament attempted to push past the police barricade, a junior police officer pushed him back, causing a melee. That evening, it was reported, the police baton-charged the people who had thronged there from far and wide after the news about the mass grave had spread.

The next morning, the Jaffna District Judge, the forensic medical expert, the Director of the Archaeological Survey, the Archaeological Excavation Officer, and various senior police officers converged on the mass grave which was under vigilant police guard. They began a detailed examination of the evidence. After eight months of analysis, this team could figure out the identities of neither the perpetrators nor the victims.

Associations for the Search of Missing Persons opined, “This mass grave is likely the handiwork of the military.” Some other organizations claimed, “The Tamil Tigers must have buried their victims here.” But neither side had any real evidence or eyewitnesses to back up their assertions. There were no gunshot wounds in any of the skulls, nor any other sign of injury. Not even a single spent bullet was found in the mass grave. Therefore, the entire investigation at the Jaffna District Court came to a standstill. The judge who was presiding over the investigation eventually retired from service.

At the beginning of this year, a person by the name Kaṉagasabai Thiyāgarām filed a petition at the Jaffna District Court. Thiyāgarām was from the village of Ūripulam where the mass grave was discovered. After the entire village was destroyed during the war, he was displaced to France. He had traveled to Sri Lanka on hearing the discovery of the mass grave in Ūripulam. His petition claimed that there was a well near the mass grave that had been filled with dirt, and that there may be more bodies buried inside the well. The petition asked for the well to be excavated. Many years ago, three brothers of Thiyāgarām’s had disappeared on the same day.

The petition came before the judges M. J. Nallaināthan and Eranga Kandewatta. They accepted the petition and ordered the well to be excavated. But it did not happen.

Thiyāgarām filed a second petition inquiring why the excavation was being delayed. When this petition came before the judges, the police explained that the well in question was built by the Village Development Council whose permission was required before excavating the well, and that the police was having difficulty locating the Village Development Council administration.

The judges did not accept this explanation by the police. They ruled to grant the police special permission for excavation, bypassing the need for express approval by the long-defunct Village Development Council, and ordered that the work must begin immediately.

Seeing that the work still was not done, Thiyāgarām filed a third petition. The police informed the court, “Work was delayed because of the rainy season.” It was fixed that the work would begin on a specific date in April.

On that day, the work did not take place because the forensic medical expert had unexpectedly gone on leave. Thiyāgarām did not give up. He filed yet another petition. This time the judges were incensed. The very next day, they summoned the officials from the thirteen government departments involved and ordered that on May 15, the well must be excavated in the presence of the two judges.

Two days before the excavation was to begin, Thiyāgarām was arrested by the secret police at a Jaffna lodge. He had spoken about the excavation at the press association in Jaffna. The police found this to be a major offense. On the grounds that it was illegal for Thiyāgarām, a French citizen, to speak to the media about local political matters in Sri Lanka, they deported him to France. Hardly anyone noticed this development. The poet V. I. S. Jayapalen was the only one who commented on the matter on Facebook. “The Sri Lankan government arrested and deported me just as they did Thiyāgarām. When my country undergoes a new dawn, sunflowers will blossom in the graveyards on our soil to welcome me back home,” he wrote with hope.

On the morning of the fifteenth of May, judges Nallaināthan and Kandewatta left Jaffna in the same vehicle and headed to Ūripulam via the Paṇṇai bridge. Both were convinced that they were carrying out their duties as judges correctly and justly. Kandewatta grasped Nallaināthan’s hand and gently squeezed it. It was a symbolic gesture meant to convey the message, ‘We will stand on the side of justice without fearing anyone. Be brave!’

Nallaināthan was the quintessential Point Pedro Tamil. Kandewatta was a descendant of Uyana Puran Appu, who rebelled against the British colonial masters in the nineteenth century. Both of them had a close, long-standing friendship. They attended Colombo Law College together and served together as lawyers at a court in Colombo. They were appointed judges on the same day. Kandewatta’s Tamil was as perfect as Nallaināthan’s flawless Sinhala. Kandewatta arrived in Jaffna in the same month as when Nallaināthan was transferred to Jaffna.

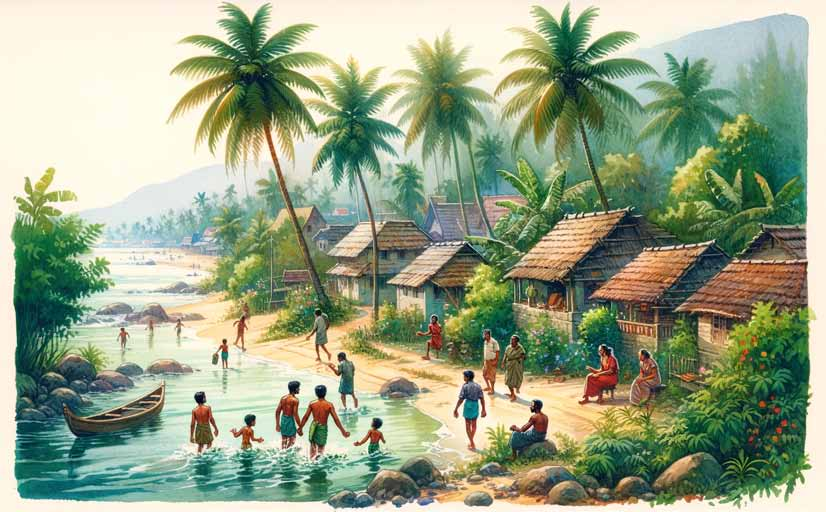

The judges’ vehicle left the Paṇṇai bridge and drove through Maṇkumpāṉ to reach Ūripulam. Nallaināthan was returning to Ūripulam after a gap of about forty years. On his previous visits, Ūripulam was a picturesque seaside village that could have been taken out of a painting. Now it was overgrown with young palm trees and shrubbery. The only evidence of prior human habitation was the small, dilapidated, low-walled Vairavar temple. Someone from Maṇkumpāṉ used to show up every day to light an oil lamp at the temple. But the discovery of the mass grave, and the subsequent round-the-clock patrolling by the police and the military had ensured that there was no longer anyone coming by every day to light a lamp at the temple.

Nallaināthan began recounting to Kandewatta his recollections of earlier visits to Ūripulam. When he was studying in Jaffna, Nallaināthan often went to the white beach with friends to bathe in the sea. One has to go past Ūripulam to get to the white beach. Ūripulam was a tiny, lone village surrounded by thick palmyra woods on three sides and the sea on the south side. The palmyra toddy from Ūripulam was considered superior even to the renowned Kūvil toddy. Whenever they visited the white beach, Nallaināthan and his friends always stopped by at Ūripulam for some toddy. When he was younger, Nallaināthan was anemic. So, he had the habit of consuming pure toddy in small amounts to strengthen his body.

Nallaināthan climbed down from the vehicle and looked up at the tall palmyra trees. They were full of dried leaves and rotten petioles. There was no sign of humans as far as the eye could see. It was an abandoned piece of land, after the entire village was shattered and its inhabitants were displaced.

Having learnt from the chaos that resulted when the mass grave was excavated the previous year, the police had arranged for heightened security. Not even a dog could wander in without their knowledge. Starting from two days prior to the planned excavation date, the police had completely barred the public or media from entering Ūripulam.

A tent had been set up next to the well with chairs and desks for the judges and other functionaries. Once the judges gave the order, the workers quickly started their machinery and got on with the excavation.

It was a parapet well with a surrounding wall. The experts who accompanied the judges surmised that there had been a thick hexagonal surrounding wall standing at the height of three feet from ground level. The wall had been demolished and pushed inside the well which had then been filled to the surface level with clay and conch soil. The machinery quickly removed the soil.

As Nallaināthan was cleaning his eyeglasses, Kandewatta leaned over to ask softly, “Do you think we will find something inside?” Nallaināthan pondered this for a while and said, “Looking at the state of this village, I think the entire village is inside this well.”

Kandewatta extended his hand to grab Nallaināthan’s and squeezed it lightly. His face had darkened. He murmured to himself, “Is there yet another unsolvable case awaiting us inside this well?”

The experts who had already estimated that the well was not deep, turned out to be correct. Within a depth of twenty feet, gaps began to be visible. Huge chunks of the surrounding wall had piled on top of one another. When the machinery lifted the wall chunks out, the water level became visible. There were moss and ferns growing along the inner walls of the well. Some aquatic plants had grown amidst these. When the machinery lifted a huge slab of concrete, something odd inside the well became visible.

Nallaināthan and Kandewatta immediately ordered the excavation to be halted. Two thick ropes were lowered into the well and two strong men climbed down the well. Once inside, they yelled out from the depths of the well with a mixture of fear and surprise:

“There is a man alive here.”

It is not important for this little story to dwell in detail on how the judges felt on hearing this, or how the forensic experts reacted, or what the Director of the Archaeological Survey guessed, or the consternation that spread among the police. Instead, let us end the first half of this story here, and proceed to the second half.

2

The horizon was turning red, and darkness was beginning to engulf Ūripulam as they lowered a long wide plank on four strong ropes and lifted the man out of the ruined well. The man was laid down on a rubber sheet inside the judges’ tent. The doctors who examined the man reported back to the judges in astonishment that he appeared to be in reasonable health. Nallaināthan gently squeezed Kandewatta’s hand. Then, he summoned a policeman and asked him to go light a lamp at the Vairavar temple visible in the distance. He then peered in silence into the darkness towards the sea. Once he spotted the tiny flame flickering into life, he let out a huge sigh.

Outside the tent, police jostled one another forming a protective ring around the tent. Doctors and archeologists sat on the chairs outside the tent and started smoking. The two judges sat on their chairs, illuminated by the soft glow of the lone lamp lit inside the tent.

The man who was discovered alive sat up slowly. The doctors had wrapped his naked body up in a new white blanket. He was taking deep breaths noisily. His two eyes set in his black face covered in a thicket of hair, rolled around like duck eggs in the low light.

Having explained in detail who they were and what was going on, the judges slowly began their judicial investigation.

“First of all, what is your name?”

“I don’t know, aiyā.”

“Don’t you have a name?”

“How can I be without a name? But since no one has called me by my name for a long time, I have forgotten it. No matter how hard I rack my brains, I can’t seem to be able to recall my name.”

“What about your parents?”

“My mother’s name is Aṉṉam. My father’s name is Chellaiyā. I have four sisters and five brothers. Since I have been thinking of them constantly, I have not forgotten any of their names.”

“How long have you been in this well?”

“I don’t know, aiyā.”

“Do you remember the date when you entered this well?”

“Very clearly. Saturday, the 22nd of August in 1990 was my twenty-fourth birthday. Already the previous evening, my younger sister had given me the hand-made birthday card she made from white cardboard. My bad luck started when I went to light the lamp at the Vairavar temple that night, Friday night, that is. As long as I was outside, I was the one who lit the lamp at the temple every evening. My family has done this for generations. My great grandfather Murukēsu had built the temple.”

“You remember all this.. But cannot remember your own name?”

“Aiyā, even as I answer your questions, I keep trying to remember my name.”

The judges were served tea. When the man was served tea, he pouted his lips to blow on the tea noisily as he drank it. The judges resumed the inquiry.

“Tell us in detail about yourself and how you came to be inside this well. But before that, finish drinking your tea.

The man set the cup with the remaining tea down on the sand and started telling his story. His was not a particularly interesting story. It was a story that had been told repeatedly. But as evidence, the story is very important to the judges as well to us.

“When I was young, I remember reading a story about a fly that had forgotten its name. My story seems to be similar. I hardly left this village. The prevailing situation in the country was not amenable to venturing outside either. I went to school until grade ten. I tried taking the grade ten examination twice but failed in all subjects. My sisters scolded me as a complete idiot, and my father called me a lazy bum. My mother said, “he is a type.” I had no interest in working or earning money. But from childhood, I was pious and had a great interest in social service. This may be hereditary. My grandfather Kadirkāmu was also said to have been very keen on public service. It was said that he was responsible for laying down the gravel road towards the white beach. Before that, there were no roads in Ūripulam.

I was at the forefront of establishing the ‘Tiruvaḷḷuvar Library.’ It may be just a thatched hut, and it may be that it received just one newspaper every day, but it was a center where the youth gathered to socialize. After fighting with the Indian Peace Keeping Force broke out, no food was delivered to the Jaffna archipelago for three months. I led the youth of the village in making porridge for the entire village every morning. We also led all sorts of other community activities like school sports meets, the Vairavar temple festival, and voluntary shramadāna activities.

After the fighting had resumed, a corpse would wash ashore at the Ūripulam seashore at least once a week. Having been in the brackish seawater for many days, these corpses would be pale and swollen. Some would have gunshot wounds. They would lie on the seashore like huge balloons, their flesh peeling off at the touch. No one would know if a corpse belonged to a Tamil, a Sinhalese, or an Indian. No one would be ready to bury the bodies. It was we, the youth of the ‘Tiruvaḷḷuvar Library,’ who would dig graves on the shore to bury the bodies.

Two youths from the village went to join a militant group in 1984. One day during the rainy season, their bodies were found in this well. No one knew if they were suicides or murders. Thereafter, no one from our village joined militant groups. The groups did not frequent the village often either.

If you asked about the military, then until August 1990, they did not set foot in Ūripulam. This was just a tiny village of a hundred huts. On the twenty-first of August, the military landed in the entire archipelago. News quickly spread that they were advancing without meeting any resistance. There was no escape in any direction. People fled their homes to seek refuge in public buildings. All of Ūripulam deserted the village to flee to the white beach. We gathered at the Guru Bawa mosque awaiting the arrival of the military. But we were confident that the military would not attack a mosque. The elders responsible for the mosque felt the same. By midday, there was no sign of the military. We had no way to know where the military was. The mosque elders arranged for lunch to be prepared in big vessels. It was there that my younger sister drew the birthday card for me. Things had normalized to a great extent by sundown that it was natural to think about birthday greetings. People thought they could spend the night at the mosque and return home in the morning.

The sun set and the reddish twilight filled the horizon. They started adhan, the call for the sunset prayer, the maghrib. When I heard that, I started to worry that my Vairavar was without a lamp that day. To leave the guard deity of Ūripulam without light on a day, a Friday at that, could bring ill fortune to the entire village. Once that thought entered my head, I left the mosque quietly, without telling anyone, and started to make my way along the shore towards Ūripulam.

The seashore was covered with thickets of screw pines and wild date palms. So, I walked carefully through them, concealing myself in the overgrowth, and checking from time to time if I could spot any sign of the military. By the time I reached Ūripulam, it was completely dark. I went into my home to pick up the bottle of oil and a box of matches and walked towards the Vairavar temple. Nothing stirred along the way.

I waded into the sea to wash my hands and feet and lit the lamp in front of Vairavar’s trident. The temple had a short wall, a small pedestal, and a single trident. It looked as if the entire village was lit up by the tiny, single flame. A great sense of calm descended into my heart. It was then that I noticed the military. They emerged from the darkness silently and stood in the lamp light. My hands were tied behind my back. I was marched to this well and was made to sit on the ground. I was not beaten or otherwise harmed. From here, I could see the flame in the temple.

I could hear the rustle of human figures moving about around me. I peered into the darkness to get a sense of what was going on. It seemed like the army was all over the landscape. A soldier came to me to ask if I wanted water. I nodded. He drew water from this very well and poured it on me. I drank like a fish. He asked me to lie down. Because my hands were tied behind my back, I could not lie on my stomach or back. So, I lay on my side and thought about the possibility of escape. There was no chance. The sounds of people walking about and conversing in Sinhala came from all directions. The distant sounds of vehicles gradually became louder. I closed my eyes. As soon as I closed my eyes, it felt like my body was glowing. I imagined that the spark I lit for Vairavar was glowing in my heart. I spent the night drawing comfort from that confidence.

Only when it was dawn could I see that Ūripulam was filled with the military overnight. I sat up slowly and looked around. There were many people lying down, or sitting up, with hands tied behind their backs. Strangely, the knowledge that I was not the only one to be detained by the military gave me a sort of comfort.

Although armed soldiers stood guard around us, they did not trouble us in any way. If one were to find fault, we could say that they did not give us food or water the entire day. Throughout the day, they brought in captives from all over the area, from Maṇdaitīvu, from Maṇkumpāṉ, from Allaipiddi, and from Vēlaṇai. They were marched here in small groups, their hands tied behind their backs. At high noon, my two brothers and some others were brought. The elders from the mosque were with them.

We spoke amongst ourselves in low voices. The military did not stop us from speaking. Some said they would interrogate us and let us leave. Some others said they would load all of us up on a ship and send us off to the dreaded Boosa detention camp.

Soon they made us sit down in nine rows because a senior military official was about to come to see us. We were eighty-six in total. The official came by and looked at us without any sign of emotion on his face. It barely took a minute. He then walked along the seashore.

A little later, I saw the soldiers drive two big machines towards us. They started digging a huge hole a short distance from us in the clay and conch soil. Dust rose above the palmyra treetops. The noise from the machines deafened us. The smoke and the smell of burning diesel nauseated us. We all understood what was about to happen.

The sun was sinking rapidly into the horizon. Judging from the dusk, it was probably around six in the evening. A large, elaborate grave had taken shape before us. The military made us line up beside it. They then asked us to climb down into the grave. There was no protest or signs of resistance. I listened intently to see if there were any sounds of crying. I could only hear the roar of the sea. The jagged line was descending into the grave. I saw my brothers climb down, looking over their shoulders at me. The mosque elder who was behind me in the line started chanting in a melodic voice. It was certainly the voice for the final prayer. I listened to the voice. It seemed like it was getting louder. My feet stepped out of the line and stopped. The elder walked past me; his voice continued to chant.

A soldier walked rapidly to where I had stepped out from the line. His eyes peered sharply at mine. He was tall, with curly hair, reminding me of my brother. As he approached me, I said:

“Let me go light the lamp for Vairavar first..”

It was clear to me that he did not understand what I said. I started walking towards the Vairavar temple. He did not stop me. I walked slowly until I reached this well. Before I could light the lamp, I needed to wash my hands and feet. Some soldiers were sitting on the wall surrounding the well. I told them:

“Please untie my hands for a while. I will light the lamp for Vairavar..”

One soldier grabbed my head, and another grabbed my feet. They lifted me off the ground and dropped me into the well. I stumbled to my feet. The water came only up to my knees. I waded over to a dark corner of the well and listened for gunshots. There was no sound of any explosion. Instead, all I heard was the giant machinery roaring back and forth. Eventually the roar approached closer. The earth started to tremble. The surrounding wall of the well was broken, and giant pieces of the wall started to fall into the well.”

Nallaināthan gently squeezed Kandewatta’s hand twice. The man draped in the white blanket resumed drinking the tea remaining in his cup.

Nallaināthan and Kandewatta deliberated the matter in hushed tones for nearly an hour. Then they went outside the tent to consult the forensic medical expert and the police officers. When they returned to the tent, they noticed that the man’s duck-egg eyes were shining brighter than before. “This man’s soul lies in his eyes,” said Kandewatta. The judges took their seats.

“Have you been able to remember your name?”

“Not yet, aiyā.”

“It is a wonder that you stayed alive for such a long time inside a well that was closed off.”

“It is no wonder. I survived there just like the water that stayed on the ground, or the plants, and frogs, and creepy crawlies that continue to live there.”

The judges were silent for a while and began to speak again:

“The war in this country ended seven years ago. Many thousands were killed throughout the war. Many mass graves have been discovered. There were atrocities committed by all sides. As you said yourself, human remains have been discovered without any hint as to whether they belonged to Tamils or Sinhalese or Indians. Peace has now come to our land after having had to get past all of these hurdles. This is the season for forgetting old hatreds.”

The other judge continued:

“Other countries are always pressing us to hold international investigations into these mass graves. But we have been insisting that internal investigations would suffice. We have already begun these internal investigations. It is as part of such an investigation that we excavated this well and discovered you. We completely accept the testimony you provided before us.

But of what use is your testimony for this land and its people? Your testimony is like ripping open and examining a wound that has been healing. If your testimony keeps digging into these wounds, how will they heal? Your testimony will only fuel hatred, not peace.”

The judge concluded firmly:

“We will not permit any attempt that can hinder reconciliation. We are not prepared to lose this peace for any reason whatsoever. You said you have a social conscience and that you have always been interested in serving the people. Therefore, we assume that you are a socially responsible good citizen. Preserving peace is your duty!”

The judges stood up to signal that the judicial investigation had concluded.

The man was lowered into the well as carefully as he was lifted out earlier. The well was closed once again. Kaṉagasabai Thiyāgarām’s petition was dismissed by the judges.

Both judges left exhausted and with heavy hearts. When the vehicle carrying the two of them started to leave, Nallaināthan asked the vehicle to be stopped for a minute. He beckoned a police officer offer to approach him, and gave him an order:

“The oil lamp for Ūripulam Vaiyravar must be lit every day without fail.”

Kandewatta took hold of Nallaināthan’s hand and squeezed it lightly.