Part-1

When I first met Matale Suneetha Thero, I couldn’t help but be captivated by his mastery of the Tamil language. His way with Tamil wasn’t just fluent; it was eloquent, technically precise, and grammatically impeccable. I was genuinely surprised to find a Sinhala-Buddhist monk speaking Tamil so fluently. My astonishment got the better of me, and I asked, “How did you become so proficient in Tamil?”With a wry smile, he replied, “Actually, you should be asking me how I became fluent in Sinhala, not the other way around. I’m Tamil, born to Tamil parents in the heart of Matale.

He continued, “There’s a common misconception that all Buddhists are Sinhalese and that Buddhism is exclusive to the Sinhalese in Sri Lanka. But that’s far from the truth. Centuries ago, before the Chola and Kalinga Magha invasions, Buddhism was the predominant religion among Tamils in Sri Lanka. While my immediate ancestors followed Saivism, I feel a deep connection to the Buddhist path, which resonates with the beliefs and practices of my forefathers.”

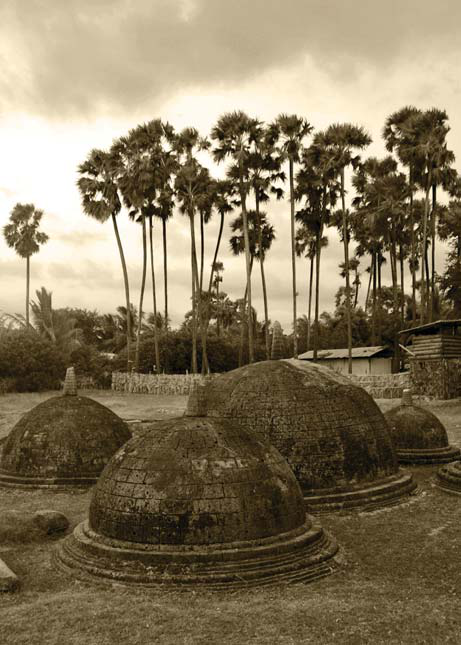

He continued. “You know, particularly in the northern and eastern regions. Now, predominantly Tamil-majority areas have a rich history with Buddhism. They were home to Tamil-speaking communities that played a pivotal role in spreading and nurturing Buddhism in the country. What’s really intriguing is that Buddhism made its mark in these parts of Sri Lanka before it reached the areas that are now predominantly Sinhalese-majority. This means that the influence of Buddhism in these Tamil-majority regions actually predates its expansion into the areas where the Sinhalese community eventually became the majority. It’s a testament to the deep-rooted connection between Buddhism and the cultural history of these Tamil-speaking regions.

He continued, “A pivotal moment in the spread of Buddhism in this region revolves around Sangamittā, the daughter of Emperor Ashoka. She undertook a remarkable mission, carrying with her a sacred branch of the Bodhi Tree—an esteemed symbol of Buddhism—from India to Sri Lanka. Her arrival took place at the ancient port of Dambakola Patuna, which we now recognize as Mathagal, situated within the Jaffna region of Sri Lanka. Arrived in Dambakola Patuna, she made her way to Anuradhapura. This remarkable journey traversed predominantly Tamil-speaking areas. As she made her way from Mathagal to Anuradhapura, her presence and the sacred branch of the Bodhi Tree, she carried profoundly impacted the local communities along the route. Many people in these areas embraced Buddhism, inspired by Buddha’s teachings and Sangamittā’s mission. This journey played a significant role in spreading Buddhism and fostering Buddhist communities in these Tamil-speaking regions.

He went on, “Indeed, it’s disheartening to see the prevailing misconception in modern Sri Lanka, which wrongly associates Buddhism solely with the Sinhalese. The real story is far more inclusive. Buddhism had a rich and enduring legacy among the Tamil population. Tamil scholars and Buddhist monks of Tamil descent have played crucial roles in spreading the profound teachings of the Buddha’s Dhamma.””As you might know,” he continued, “the Five Great Epics—Silappatikāram, Manimekalai, Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi, Valayapathi, and Kuṇṭalakēci—are treasured in Tamil culture. Manimekalai and Kuṇṭalakēci were crafted by Buddhists, while the other three were composed by Tamil Jains. Interestingly, Tamil Saivites did not contribute any epics in this context, underscoring the diverse religious landscape of ancient Tamil society.””Furthermore,” he emphasized, “it’s crucial to grasp a fundamental aspect. Buddha explicitly stated that his teachings should transcend any specific race or religion. He vehemently opposed the creation of any religious sect in his name. Instead, he offered the Dhamma—a universal way of life. His teachings and his Dhamma, are intended for all sentient beings, transcending any particular ethnic or cultural group. It’s vital to recognize this universal aspect of Buddhism and wholeheartedly embrace its inclusive nature.”

He took a deep breath, momentarily interrupting his extended monologue.

To be continued.