It can be firmly stated that no other Sri Lankan has been subjected to global scholarly scrutiny to the extent that Ananda Coomaraswamy has. No other multi-talented Sri Lankan scholar has achieved such worldwide fame. Despite the vast knowledge available globally about Ananda Coomaraswamy, it is evident that there have not been comprehensive records about the remarkable women who were his wives. Through their lives, it becomes clear that Coomaraswamy’s love and involvement with these women were not merely due to physical attraction or sexual desire. Ananda Coomaraswamy significantly supported and refined the personalities of these four women.

Similarly, the contributions of these four women were indispensable to the success of all of Coomaraswamy’s work. He collaborated with all four of them in his artistic and literary endeavors. He effectively utilized their talents in his artistic, literary, and research activities. The works he created in this manner were published with the names of his wives alongside his own.

In other words, it is reasonable to question whether Ananda Coomaraswamy could have achieved worldwide fame or accomplished so many works and achievements without the support of these four women. However, detailed records about these women are not available as a comprehensive collection anywhere. Instead, it is necessary to gather information piecemeal from various books and articles, extracting bits from here and there.

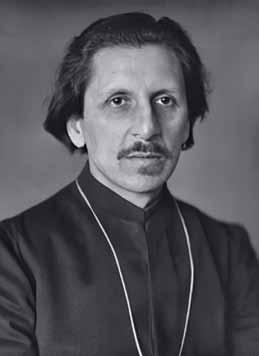

Ethel Mary Coomaraswamy

Ethel Mary Coomaraswamy (Ethel Mary Mairet, February 17, 1872 – November 18, 1952) is globally known as a British handloom weaver. When discussing the development of handicrafts in the first half of the twentieth century, it is impossible to overlook Ethel Mary’s role.

Ethel Mary Partridge was born in 1872 in Devon, England. She was educated domestically and later qualified to teach at the Royal Academy of Music in 1899, specializing in piano.

She married Ananda Coomaraswamy on June 19, 1902. At that time, Ethel was five years older than Ananda Coomaraswamy. The couple traveled to Sri Lanka, where Ananda Coomaraswamy joined a mineral research project. During this period, he wrote several articles on Sri Lanka’s mineral resources, which were published in various scholarly journals. His research began in this field. They stayed in a bungalow near the city of Kandy. The couple documented the arts and crafts of every village they visited. They recorded details about each craft they observed and took photographs. After five years, they returned to England in 1907 and published their research on Sri Lanka’s handicrafts.

Until 1910, they lived in Broad Campden. There, they collaborated with artisans like the architectural craftsman Charles Robert Ashbee to form and operate a group of craftsmen. Later, the couple revisited India and Sri Lanka to continue their artistic work.

Ethel independently learned the arts of weaving, dyeing, and spinning yarn. At a time when weaving by women was limited to household needs, she presented it as an art form and a professional craft. She became a significant role model for women interested in weaving and gained fame in the field.

In 1909, Ethel returned to England and conducted her first experiments in weaving and dyeing in Campden. She studied books on vegetable dyes at the Bodleian Library in Oxford and sought out places to learn weaving. Her knowledge of dyeing and creating color patterns through sewing might have been influenced by her father, a chemist, and her husband, Ananda Coomaraswamy, a botanist.

In December 1910, Ethel and Ananda Coomaraswamy traveled to India to continue their artistic work and research, writing about their discoveries. In 1910, Coomaraswamy openly engaged in another romantic relationship, which led to the end of his marriage with Ethel.

Ethel later built a house near Barnstaple with studios for dyeing and weaving. In 1913, she married Philip Mairet, and together they established The Thatched House, a communal home and studio. Her dream of a weaving workshop became a reality. Mahatma Gandhi visited her the following year, knowing about her work in Sri Lanka and India. Gandhi was keenly interested in using simple techniques for spinning khadi cloth in India.

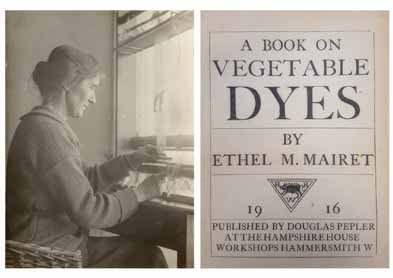

In 1916, she published a book titled “A Book on Vegetable Dyes” in London, which is still celebrated as one of the pioneering books in the field. In 1917, she revised and expanded the book with additional details.

During the 1930s and 1940s, she provided training in weaving and dyeing at her studio, passing on her expertise to the next generation of artists.

Her dedication and innovation in the field brought her recognition in many countries. In 1937, she received the Royal Society of Arts honorary award, becoming the first woman to receive this honor. 1939 she published “Handweaving Today” and taught at the Brighton School of Art from 1939 to 1947.

Throughout her life, Ethel remained active in her field, continuously guiding students and sending samples of her work to schools nationwide.

She married Ananda Coomaraswamy on June 19, 1902, but they divorced in 1913. Ethel passed away in 1952 and was buried at St. Nicholas Church in Brighton.

Ethel Mairet continues to influence generations of weavers. Her biography in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography refers to her as the “mother of English handloom weaving.” Her works are still displayed in museums, along with documents and memorabilia from 1872-1952. These include personal documents, travel journals from 1910-1938, commercial and personal correspondence, account books, and photographs. Her works are still part of educational curricula today.

Translator of the Mahavamsa

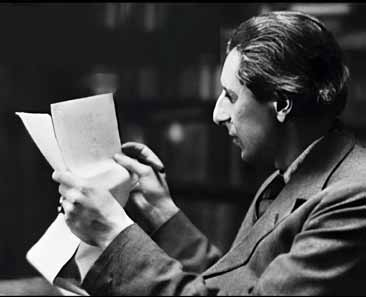

Although Ananda Coomaraswamy had a family background of Jaffna Tamil and English heritage, he is predominantly celebrated by the Sinhalese Buddhist community today. His research is still admired not only in the Eastern world but also in the Western world. His role in introducing Eastern arts, cultures, and literatures to the West is extensive.

In Sri Lanka’s government school curriculum, the 9th-grade Sinhala language textbook includes 12 pages about Ananda Coomaraswamy. Even in Tamil textbooks, there is not as much detailed information about him. His works and books written in English have been translated into many languages. Most of his books have been translated into Sinhala, whereas only a few have been translated into Tamil. In other words, Ananda Coomaraswamy is not as well known in the Tamil community as he is in the Sinhalese community.

No other Sri Lankan has conducted as extensive research on Sinhalese heritage, culture, and literature as Ananda Coomaraswamy. This is why his works on the rediscovery of Sinhalese Buddhist community history are still celebrated by the Sinhalese community today.

In 1905, Wilhelm Geiger first brought the “Dipavamsa Mahavamsa” from Pali into German. Within the next three years, Ethel Mary Coomaraswamy translated it into English. Subsequently, Wilhelm Geiger, with the assistance of Mabel Haynes Bode, translated the Mahavamsa separately, which was published in 1912. Thus, the history of the Mahavamsa shows its translation from Pali to German, from German to English, and finally from English to Sinhala. While the names of everyone involved in the translation of the Mahavamsa, from Geiger to Mabel Haynes Bode, are deeply etched in history, Ethel Coomaraswamy, who first translated it into English, is not mentioned in any subsequent editions of the Mahavamsa. It is surprising to note that even in the 6th volume of the Mahavamsa published by the Sri Lankan government, while all the aforementioned names are mentioned, Ethel’s name is conspicuously absent. Notably, she is not acknowledged anywhere in Sinhala records.

Moreover, Wilhelm Geiger did not mention Ethel’s assistance in the translation anywhere in the “Dipavamsa Mahavamsa.” Due to the lack of records acknowledging Ethel’s contribution to the Mahavamsa, her involvement is not even mentioned in the book “A Weaver’s Life: Ethel Mairet 1872-1952,” which elaborates on her life.

In the same year, 1908, Ananda Coomaraswamy’s book “Mediaeval Sinhalese Art” was published. It was his first book. Ethel’s translation of the Mahavamsa had already been published before that. The book “Mediaeval Sinhalese Art” is a significant work celebrated by the Sinhalese community. In this book, Ananda Coomaraswamy references the Mahavamsa in many places. The Sinhala edition of this book has seen many reprints over the years. It is noted in textbooks for its historical importance as the first book to place Sri Lanka’s artistic heritage on the world map.

His works and his contributions are considered significant in various university curricula. Notably, more is taught about him in Sinhala language textbooks than in Tamil language textbooks.

He married Ethel Mary in 1902 and lived with her until 1913. Despite being together for 11 years, they did not have any children. In 1907, Alice Ethel joined the Coomaraswamy couple’s art group to work with them during this period. The following year, Ananda Coomaraswamy began a romantic relationship with Alice. Finally, Ananda Coomaraswamy openly told his wife, Ethel, that he intended to marry a second time. Ethel, who had not expected such a revelation, was shocked and left the house upon hearing it.

Apart from the articles she co-authored with Ananda Coomaraswamy, Ethel’s books can be listed as follows:

- Old Sinhalese Embroidery. 1906

- The Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa and Their Historical Development in Ceylon by Geiger Wilhelm; Translated into English by Coomaraswamy M Ethel, C. Cottle (Colombo) Government Printer, Ceylon, 1908

- A Book on Vegetable Dyes. Douglas Pepler at the Hampshire House Workshops, Hammersmith, gutenberg.org. (1916)

- Hand-weaving Today, Traditions and Changes: By Ethel Mairet,… Faber and Faber. (1939)

Ratan Devi (1913–1922)

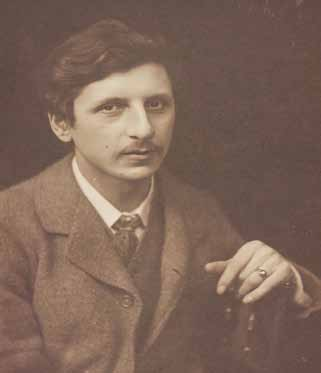

Ananda Coomaraswamy’s second wife, known as Ratan Devi, was actually Alice Ethel Richardson. Seeing that name, one might assume she was Tamil, but that is not the case. Ratan Devi’s real name was Alice Ethel Richardson, and she was born in England in 1889. Ananda Coomaraswamy and Alice had two children, a son named Narada Coomaraswamy and a daughter named Rohini Coomaraswamy.

Ananda and Alice lived on a houseboat in Srinagar, Kashmir, India. Coomaraswamy studied Rajput painting, while Alice learned Indian music from Abdul Rahim of Kapurthala. As a result, in 1916, she published two volumes titled “Rajput Paintings.” Upon their return to England, Alice performed Indian songs on various stages under the name “Ratan Devi.” During this successful journey, they undertook many tours, where Alice would sing after Ananda Coomaraswamy’s speeches.

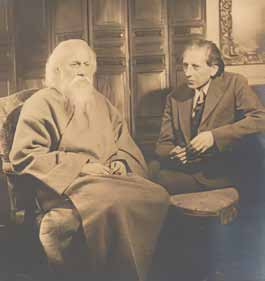

In 1913, Ananda Coomaraswamy and Alice co-authored and published the book “Thirty Songs from the Punjab and Kashmir.” They dedicated this book to their eldest son, Narada, whom they had long awaited. This book boasts two notable features: first, the songs include musical notation; second, the introduction was written by Rabindranath Tagore. During Ananda Coomaraswamy’s visits to Calcutta, he stayed with Tagore as his guest. Tagore wrote a laudatory introduction about Alice’s singing. The book received excellent reviews not only from newspapers but also from renowned personalities such as composer Percy Grainger, playwright George Bernard Shaw, and poet W.B. Yeats.

Additionally, Ratan Devi published another book titled “Book of Words of Classic East Indian Ragas and Kashmiri Folk Songs Sung by Ratan Devi (Mrs. Ananda K. Coomaraswamy) in her Costume Recitals.” This was published in New York by the J. B. Pond Lyceum Bureau.

On October 14, 1916, the renowned American magazine Musical America mentioned the Kashmir music journey of Ananda and Ratan Devi as follows:

In the latter half of 1915-1916, one could witness the very interesting music programs featuring East Indian traditional ragas and Kashmiri folk songs by Ratan Devi and Dr. Ananda Coomaraswamy. The interest in these artists was so high that they could not meet all the demands. Therefore, they have decided to undertake a second American tour, which will begin on January 1.

In the same year, 1916, another American magazine published a detailed article about Ratan Devi’s work in understanding, experiencing, and promoting Indian music. The article praised her elegance in playing Indian music on the piano. Considering the news and articles published in various American magazines, it is evident that their contribution to introducing Eastern music, particularly Indian music, to Western audiences over a century ago is significant. Their work continues to be referenced in many studies today.

By 1917, their marital life had fractured. They initially lived separately and later divorced formally. Ananda Coomaraswamy explained his philosophical understanding of marriage and the reasons for his divorce in his book “The Dance of Shiva,” under the essay titled “The Status of Indian Women.” He further explored his views and quests regarding domestic life and renunciation in his philosophical writings. His books like “Buddha and the Gospel of Buddhism” serve as examples of this exploration.

Stella Bloch

Ananda Coomaraswamy’s third wife, Stella Bloch, married him in 1922 when she was 25 and he was 45, a 20-year age difference. They lived together until 1930. Born in 1897, Stella was an American dancer, journalist, and talented painter. She passed away on January 10, 1999, just before her 101st birthday, having lived for 71 years after their divorce.

Stella Bloch met Ananda Coomaraswamy in America when she was 17 years old. She traveled with him to learn about Eastern arts. They visited countries like Bali, Cambodia, China, India, Java, and Japan to learn about the arts there. During this period, it was Ratan Devi who taught her Indian dances.

Some of the famous photographs of Ananda Coomaraswamy were taken by Stella Bloch. Similarly, a well-known photograph of Stella that still exists today was taken by Ananda Coomaraswamy. Stella Bloch wrote and published a book titled “Dancing and the Drama East and West” in 1922, the same year they got married. The cover of this book bears the words “With an Introduction by Ananda Coomaraswamy.” However, the introduction inside is dated 1921, indicating it was written a year before their marriage.

Though the book is quite short, with only 38 pages, after excluding the blank pages, Ananda Coomaraswamy’s 3-page introduction, and the 8 individual pages with illustrations, the actual content is just 13 pages. This short essay, containing fewer than 2,400 English words, was published as a book. All the line drawings in the book were done by Stella herself.

After separating from Coomaraswamy in 1931, Stella married American lyricist, producer, and actor Edward Eliscu. She wrote numerous research articles and produced many works while working at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Her paintings were used as logos for African American music productions, and her artworks are preserved at Princeton University and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Viswanath, who wrote a book about her, noted that her house in Needham, Boston, was like a museum, filled with art objects from around the world.

The details of the five articles she co-authored with Ananda Coomaraswamy can be found in a compilation of Coomaraswamy’s works prepared by Dr. Rama Ponnampalam Coomaraswamy.

Examples of Stella’s books and articles include:

- Introduction to Dancing and Drama in East and West by Stella Bloch, New York, 1922.

- The Appreciation of Art (with Stella Bloch). The Art Bulletin, (Providence, R. I.), VI, 1923, pp. 61-64.

- Medieval and Modern Hinduism (with Stella Bloch), Asia, (New York), XXIII, No. 3, 1923, pp. 203-206 and 230, 4 figs.

- The Chinese Theatre in Boston (with Stella Bloch), Theatre Arts Monthly, (New York), IX, February 1925, pp. 113-122.

- The Javanese Theatre (with Stella Bloch), Asia, (New York), XXIX, 1929, pp. 536-539, 6 figs. Reprinted in Baker’s Drama Gram, (Boston), VII, 1929, pp. 15-17 (as an abstract and without illustrations).

Luisa Runstein (Dona Luisa Runstein)

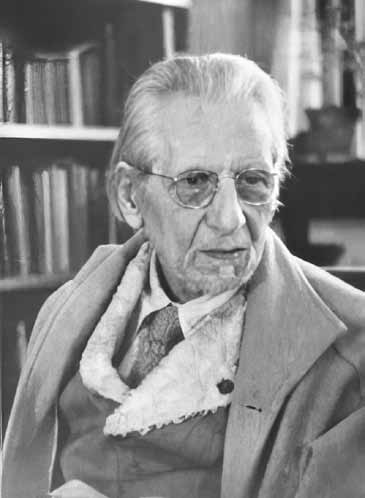

In the same year, Ananda Coomaraswamy divorced Stella, and he married Luisa Runstein from Argentina, with whom he lived until he died in 1947. They had a 28-year age gap. Coomaraswamy met Luisa at a communist protest in Cambridge. Her parents were Jewish immigrants to Argentina, and she came to America at 16. Known as Xlata Llamas (Lotte Lamas), she was a prominent photographer.

Many of the photographs of Ananda Coomaraswamy that we have today were taken by Luisa. Her photography collection also includes beautiful photographs of Rabindranath Tagore. Some of these photographs were signed by Tagore himself. It is also known that the famous picture of Stella Bloch, Ananda Coomaraswamy’s third wife, was taken by Luisa. Likewise, Luisa took the well-known side profile photograph of Ananda Coomaraswamy wearing a hat and leaning down, which was taken in 1937.

At that time, Luisa was only 25 years old. Their son, Rama Coomaraswamy, was born two years after their marriage. They lived for many years in a house near Boston. Although Rama completed his early education at a conservative Hindu school in India, he later pursued higher education in the medical field and became a renowned doctor. Additionally, he converted to Christianity. He lived in countries like the United States and Canada for some time before moving to England, where he completed his postgraduate studies at Oxford and Harvard Colleges. He authored and published several research books on Christianity. Rama passed away in 2006 at the age of 75.

Luisa cared for Ananda Coomaraswamy with great concern until the end. She was also his assistant, helping with office work and research. It is noted that Luisa learned Hindi and Sanskrit in India. After Ananda Coomaraswamy’s death, Luisa served as a guide to many who researched his works.

Ananda Coomaraswamy passed away on September 9, 1947, in America. His funeral was held at a Christian church, where eulogies by Luisa and their son, Rama Ponnampalam, were delivered. These speeches were later published in a memorial volume in 1952, five years after his death. The book, which contains 420 pages, includes tributes and articles from various individuals, including the then Prime Minister of Sri Lanka, D.S. Senanayake. It was compiled by Durairajasingam. In her eulogy, Luisa said:

“Coomaraswamy spent his entire life learning, seeking knowledge, and continuously striving to understand himself. In all these pursuits, our deep interest acted as iron particles and your love, as the magnet that drew us in.”

It is unfortunate that detailed and clear records of Luisa’s life, who lived with Ananda Coomaraswamy for the last 17 years of his life, are not readily available. Those who wish to search for her photographs and articles can look under the name Zlata Llamas.

Luisa was not only known as an excellent photographer, but her articles published in some research journals under the name Dora Luisa Coomaraswamy also reveal her profound depth as a creator.

Luisa passed away in 1969 at the age of 65