V.V. “Sugi” Ganeshananthan, an American fiction writer, essayist, and journalist of Srilankan Tamil descent, is a formidable presence in modern literature.

Her debut novel, “Love Marriage” (2008), juxtaposes the landscapes of Sri Lanka and North America, intricately weaving the impact of Sri Lankan politics on familial dynamics. This lauded work was honored among The Washington Post Book World’s Best of 2008 and longlisted for the Orange Prize, establishing her as a literary tour de force.

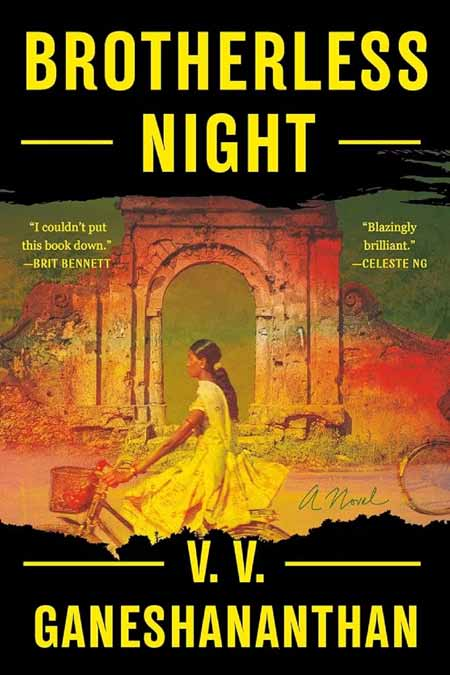

“Brotherless Night” (2023), her magnum opus, unfolds against the backdrop of the early Sri Lankan civil war, chronicling the trials of sixteen-year-old Sashikala “Sashi.” This poignant narrative, earning the 2024 Carol Shields Prize for Fiction and a shortlist spot for the Women’s Prize for Fiction, further solidified her literary eminence.

Ganeshananthan’s illustrious academic journey includes a Harvard College degree, an M.F.A. from the University of Iowa, and a master’s from Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. As a revered educator, she has imparted wisdom at the University of Michigan and the University of Minnesota.

Her contributions transcend academia; she has served as vice president of the South Asian Journalists Association and holds board positions with the Asian American Writers’ Workshop and The Harvard Crimson.

Excerpts from Our Interview with V.V. Ganeshananthan

How do you feel about giving an interview to a magazine based in Jaffna, a place with which you have a hereditary connection?

I’m always thrilled to talk to people in Jaffna or those who care about Jaffna! Thank you for reaching out to me.

Can you share more about your research process for “Brotherless Night”?

I read extensively—books by authors from many different vantage points and communities. This included scholarly and journalistic accounts, memoirs, and general histories. I also interviewed many people who lived through this period. In this way, I hope to understand both the incompleteness of each story and its specific truth.

How do you approach character development, especially when dealing with historical and political contexts?

The people I read about and spoke to were affected by politics, and so am I. I’ve been influenced by events like the election of Barack Obama, the election of Donald Trump, 9/11, and the pandemic. By reflecting on how political and historical events in my lifetime have impacted me, I could imagine how political events of the 1980s—such as the burning of the Jaffna Public Library—affected my characters.

The people I interviewed provided specific details about their relationships to events that history books now regard as major occurrences, often described with considerable distance. The library burned, but many people were employed there, studied there, and loved its collections. When my character Dayalan works there, he develops a very distinctive relationship with history, as do his siblings who study at the library.

Your book includes some details that differ from historical or factual accounts, such as the inclusion of practical tests in A/L exams and the idea that it is rare for someone to top the island on their first try. How do you view the role of such creative liberties in your storytelling? How do you balance the need for factual accuracy with the creative freedom of fiction, and what challenges do you face in maintaining this balance?

…I tried to be as factually correct as was interesting.” That’s from the beginning of Gerontius by James Hamilton-Paterson. A beloved teacher of mine used to quote that to us, and I heard it around the time I started working on this book. The facts as they stand are interesting to me, or I wouldn’t have been drawn to this moment in history, but I knew I wasn’t going to represent them precisely; that would mean I might as well have written nonfiction. I generally tried to know when I was sticking to the facts and when I wasn’t, but sometimes I thought I had invented something, only to discover that something very close to my creation had occurred. That was always curiously satisfying—a sign that somehow I’d marinated in the research so much that my subconscious knew what had occurred even when my conscious self did not. Of course, the opposite sometimes occurred, too: I would think I had portrayed something accurately, only to have someone tell me I had aimed and missed.

All that said, people’s preferences on this point—facts in fiction, historical accuracy in fiction—vary quite a lot and in ways that are difficult to predict. So, in the end, the measure I had to use was my own interest and satisfaction. What facts did I want to include, even on an inarticulable level? How could I know and verify them? Which details were more malleable or represented emotional truths that were valuable to the story? The practical exams are a good example. I personally hate dissection and have also heard many stories from people who belonged to earlier generations and had to do practical exams. So I had spent a lot of time imagining that and wanted to put it in. That had the added benefit of foreshadowing some choices and challenges Sashi faces later on in the story.

You chose to write about events and experiences that you did not personally live through. What perspectives and insights do you believe you bring to literature by writing from second-hand experiences? Although you did not live through the events described in your book, do you have any personal connections or experiences that influenced your writing?

A good deal of historical fiction is written by people who did not live through the periods they depict and who are working with some amount of distance in terms of time and place, so in that regard, when I began the project, I knew I was not unusual. And I felt that Jaffna in the 1980s was as worthy of that kind of scrutiny as any other period. I did think that my ties to the community—the hereditary connection to which you refer—and my specific training as a journalist and fiction writer might mean that I could aim to create a depiction that offered both broad historical perspective and intensely individualized details. I had grown up with some stories about this time and place and accounts shared by people in my community, and those piqued my interest, so I wanted to learn more.

The book offered an unparalleled opportunity to achieve that. Some measures of distance were useful, and so was collapsing that distance, which I was able to do with the aid of people I already knew and others I met during the course of studying this period. In other words, I felt that my inherited understanding and connections were enough to push me to begin, but they left me with enough questions that I wanted to write the book. I did not know in advance how it would turn out, and if I had, I wouldn’t have needed to write it.

Do you have any plans to write about the second-generation Tamil diaspora, a demographic of growing importance with which you have firsthand experience?

The main character and storyline of my first novel, Love Marriage, are diasporic. It’s possible I will return to that landscape at some point, but I will probably go on to new terrain first.

What impact do you hope your book will have on readers, both within the Tamil diaspora and beyond? What themes do you want them to take away?

My feelings about the book aren’t quite so directed, but on the most basic level, I hope people understand it as an invitation to engage with history and the present. Which version of the story did you know? What other versions might exist? I hope people think about who explains history, who is expected to explain it, which tellers we trust, and why. Who has authority? Who do we think is the audience for a story like this one? What do we expect of them? Why does that include or exclude you, and what kind of power does that give you?

What kind of feedback have you received from the Tamil community and other readers regarding your portrayal of the civil conflict and its aftermath?

Most strikingly, I’ve heard from a number of Tamil readers who told me that the book made space for their families to talk about things like Black July or the war when they hadn’t previously done so. I didn’t expect that, and it really astonished me the first time I had a friend say that my parents and I never talked about this openly until we all read your book, even though my family was affected by what happened. In some cases, I learned that people I had thought comparatively removed from the war had actually had close experiences of violence.

People have also offered surprising and persuasive interpretations that have taught me about my own work. I’ve been especially happy to hear from Tamil speakers and Tamil heritage speakers who see the influence of Tamil in my English sentences.

Who or what are your major influences and inspirations in writing, particularly in relation to “Brotherless Night”?

I’m an admirer of A. Sivanandan, Shyam Selvadurai, Romesh Gunesekara, and Shoabsakthi. I also love the work of Jamaica Kincaid and Elizabeth McCracken, as well as writing by Jo Ann Beard, Rohini Mohan, Meera Srinivasan, Namini Wijedasa, Yiyun Li, James Alan McPherson, Colson Whitehead, and Michael Chabon. You can see how I’m mixing nonfiction and fiction writers together here! When I was writing Brotherless Night, I repeatedly turned to The Broken Palmyra and other works by members of University Teachers for Human Rights (Jaffna). I am particularly grateful for the words of Rajani Thiranagama and Rajan Hoole, from which I drew the epigraphs of Brotherless Night.

You have visited Sri Lanka and Jaffna recently. How do you see the positive and negative aspects of these places and the people?

I love traveling to Sri Lanka and Jaffna, but my recent travels have been somewhat constrained, so I can’t generalize too much. I was most recently in Colombo, Kandy, and Jaffna, so I don’t know much about what’s going on in the East or South. I saw many ordinary Sri Lankans struggling with the increased costs of living and experiencing the effects of climate change. I also noticed increases in traffic and construction, as well as a sizable military presence that remains a decade and a half after the end of the war. Despite all this, people are doing their best to organize and improve their circumstances. I am heartened to see that some conversations are occurring across the usual divides, though there is still more work to do.

As a writer, can literature build a bridge between the Tamil and Sinhala communities?

I think literature is important, but it is not sufficient on its own. Literature cannot replace political will, good governance, or peace with justice and security for all communities. However, I do hope it helps people to imagine a better society, which is at least a beginning.